Chapter 2

Money Market

Lets begin with the kindergartner’s explanation. A market is a place where buyers and sellers meet to trade. When a person needs food, he goes to the supermarket to purchase groceries (trading money for products); hence he is a “consumer” or “buyer.” A farmer produces food and sells it to the supermarket; hence he is a “producer” or “seller.” Your friendly grocer is an intermediary (middleman) who provides a valuable service for which he is compensated. Without the supermarket it would be a terrible hassle to visit a ranch to buy beef, a baker to buy bread, etc. A common name for our money market (there is only 1 market for the world) is “Wall Street”, and it serves the same basic function as your local grocery store.

A person who has too much money, more than he or she can spend immediately, needs to save it for future use. He is called a “saver,” “lender” or “investor.” This individual is motivated by self-interest to get the best deal possible. This means selecting the financial instrument (from all that are available) with the least risk and highest returns on investment. A person who needs money (a “borrower”) must create an IOU (financial instrument) with terms that may include interest and promises to keep the money as safe as possible. The borrower must fashion his IOU to be more attractive to investors than his competition, the IOU’s of other borrower. However, the self-interest of the borrower is to provide the least security along with the lowest returns, exactly the opposite of the interest of the lender. Savers and borrowers can use an intermediary, like a bank, or they can deal directly with one another. In any case, the philosophy of a money market is simple… people trade money for financial instruments (IOU’s). Since an IOU is not tangible, the money market requires faith in order to operate. If savers lose confidence in markets, they will refuse to purchase IOU’s and the economy will grind to a screeching halt.

The competing self-interests of savers and borrowers creates two basic problems:

1. How can savers compare competing IOU’s on a basis that enables them to select the best one (i.e. apples to apples)?

2. How can borrowers be prevented from lying?

The answer to both of these questions is that an imperfect quilt of public laws and regulatory bodies coupled with private organizations and “market forces” attempt to create a level playing field for the money market. This course deals with one significant portion of the patchwork; the rules surrounding the preparation and presentation of financial statements. The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB”) describes itself as follows:

Since 1973, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has been the designated organization in the private sector for establishing standards of financial accounting that govern the preparation of financial reports by nongovernmental entities. Those standards are officially recognized as authoritative by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) (Financial Reporting Release No. 1, Section 101, and reaffirmed in its April 2003 Policy Statement) and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (Rule 203, Rules of Professional Conduct, as amended May 1973 and May 1979). Such standards are important to the efficient functioning of the economy because decisions about the allocation of resources rely heavily on credible, concise, and understandable financial information.[1]

In short, the Securities and Exchange Commission[2] (“SEC”), the U.S. government’s financial market regulatory body, and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants[3] (“AICPA”), the professional association of U.S. Certified Public Accountants, both follow FASB pronouncements as authoritative, i.e. accounting law. This textbook is primarily dedicated to teaching you the language and mechanics of GAAP.

If a borrower wishes to sell an IOU to the general public, the SEC will likely have regulatory authority (there are some exemptions) and may require a financial statement audit by a licensed CPA to attest that the statements are materially correct under Generally Accepted Accounting Rules (“GAAP”) as proclaimed by the FASB. Even if a borrower wishes to enter into a private transaction that is not governed by SEC rules, it is likely that the investor will demand audited financial statements in accordance with GAAP. This is a pretty sweet deal for the CPA profession. If a borrower wants access to money markets for anything other than routine personal business (home mortgage, credit card or student loan), they will probably need to hire a CPA. Please consider and discuss these issues with your classmates:

1. Who benefits from the work of the FASB?

2. What are the benefits of the FASB being a private organization? Would the FASB produce different work if it were part of our democratic government?

3. Should FASB expand its role by setting standards on information other than financial accounting?

There are no right and wrong answers to these questions. Please consider both sides of every argument as well as possible unintended consequences of any changes to the current financial accounting paradigm.

The Limited Importance of GAAP Financial Statements: Table 2.1

While financial reports (which include financial statements) are important, they are certainly not the only source of relevant information for investors comparing competing financial instruments issued by different companies. In some cases, one may conclude that other than the price of admission to access public financial markets, they are relatively insignificant when compared to the universe of other available information. In the following table you can see a comparable financial instrument (common stock), across various companies, compared to their net assets (assets-liabilities) and tangible net assets (assets-intangible assets-liabilities) in accordance with GAAP.

If GAAP financial statements were the only relevant variable that investors considered, then all companies would receive the same relative price for their common stock (e.g. price/earnings ration or market cap/net assets ratio). As you can see in this table, the financial market values accounting assets quite differently. The market values every $1 of net tangible assets of Exxon Mobile at $2.77 while $1 of Apple, Inc’s net tangible assets is valued at $6.64. Both Apple and Exxon are required to account for their assets using the same rules.

Apparently the market considers factors other than GAAP financial statements when valuing common stock. In some cases factors such as exponential forecasted growth or decline, major technological changes (Kondratieff Waves) or environmental factors can turn financial reports into useless “noise.” However, these incidents would be exceptions to normal day-to-day business operations. In the normal course of business, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles creates a common language that facilitates an efficient money market. Consider the analysis presented in Table 2.1. All of the numbers in this table were pulled from financial reports prepared in accordance with GAAP. Furthermore, the financial reports were audited by a Certified Public Accountant and received unqualified opinions (clean audit opinions). This enables us to make an apples to apples comparison between companies from any industry.

Both tangible and intangible assets were presented in Table 2.1 for the reader to consider. Tangible assets are items that an organization generally purchases for money that have physical matter (desk, chair, computer, etc.) while an intangible asset generally is something without physical matter that is purchased by a company for money (patent, non-compete agreement, customer list, etc.). An intangible that a company develops on its own, for example the trademark Coca Cola, has no value on The Coca Cola Company’s books. But, if Coca Cola Company purchased the trademark for Mountain Dew, it would record the intangible asset at its purchase price (Historical Cost Principle). The largest intangible asset on General Motors’ balance sheet is Goodwill, an intangible asset that is created in when one company purchases another and pays more than the price of the tangible and identifiable intangible assets. We will not study the specifics of goodwill in this text; it is a subject for an advanced accounting text. I highlight it to make a point about how FASB creates rules. While the members of the FASB are just like you and I, fallible human beings, they are guided by declared Assumptions, Principles and Constraints[1]. All rules must comply with these guiding declarations… unless of course a declaration gets in the way of something the FASB or its constituents (SEC and AICPA) want to do. This is what happened with the rules surrounding accounting for Goodwill. Goodwill, unlike almost every other asset is not accounted for using the Historic Cost Principle, instead the FASB adopted a new approach, the Fair Value Principle.

In this textbook I will take a different approach to teaching the FASB Concepts Statements and FASB’s Assumptions, Principles and Constraints. Rather than teaching them as a separate subject area, I will present them as they relate to a subject area that I am teaching, a markedly different approach from most textbooks.

In this textbook I will take a different approach to teaching the FASB Concepts Statements and FASB’s Assumptions, Principles and Constraints. Rather than teaching them as a separate subject area, I will present them as they relate to a subject area that I am teaching, a markedly different approach from most textbooks.

Kuhn: Normal Science

Paradigms create boundaries that restrict the thoughts of its members. In effect, people are forced to think within the framework in order to function in their community. For example, a chemist must communicate with his colleagues using the language of the imperfect Periodic Table of Elements. Kuhn (1996) concedes that this is a limitation imposed by paradigms, but he argues the benefits outweigh the limitations.

Ought we conclude from the frequency with which such instrumental commitments prove misleading that science should abandon standard tests and standards instruments? That would result in an inconceivable method of research. Paradigm procedures and applications are as necessary to science as paradigm laws and theories, and they have the same effects. Inevitably they restrict the phenomenological field accessible for scientific investigation in a given time (p. 60).

The words “in a given time” are profound for if a given paradigm is not replaced by an improved paradigm, it is a sign that scientific advancement has stopped. But abandoning a paradigm because it has problems in the hope that a better one will eventually come along is nonsensical because it is the knowledge gained in the current paradigm that leads to scientific revolution and paradigm replacement.

Once the paradigm is established, advancement within the paradigm occurs through experimentation and refinement that Kuhn calls “Normal Science.” In science, the paradigm creates a language and boundaries that enable its practitioners to apply its principles to different real world scenarios and communicate findings. For example, in the early 1950’s, Watson and Crick, both of whom were accomplished molecular biologists, discovered the double helix structure of DNA while performing Normal Science in the field of molecular biology. Within 50 years, using the language created by Watson and Crick to describe their new scientific paradigm (A:T C:G), genetic scientists were able to map the human genome, a scientific breakthrough that could change the future of mankind. Please read Chapter Three of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions to investigate how Kuhn describes Normal Science. The purpose of this textbook is to help you learn the language and rules of the financial accounting paradigm so you can become an accounting scientist, or at a minimum, understand what financial accountants are telling you.

Financial Statements: Communicating With Standardized Language

Recall the U.S. Census Department sponsored survey regarding worklife earnings http://preview.tinyurl.com/3hlvzue presented in Chapter One. A major weaknesses that you may have identified in this report is that its dependent variable[5], Synthetic Worklife Earnings, is a future estimate based on historic information. Furthermore, the categorization of the independent variables may cause the reader to make an incorrect decision based on the report (“If I earn a Juris Doctor degree from Podunk U., I am going to be rich”). Even though this report was subjected to peer review, its research design and final report were not based on a standard set of rules issued by an authoritative[6] body. If a reader wished to compare this report to any other report correlating educational achievement to future earning power, he or she would need to study the methodology and definitions used in both reports, then decide the best way to reconcile the reported findings. As more reports were read, the complexity of this task would grow exponentially. The FASB (or International Accounting Standards Board[7] “IASB”) attempt to solve this incompatible information problem so savers can easily make apples to apples comparisons on certain tightly defined variables.

FASB declared the following:

OB2. The objective of general purpose financial reporting is to provide financial information about the reporting entity that is useful to existing and potential investors, lenders, and other creditors in making decisions about providing resources to the entity. Those decisions involve buying, selling, or holding equity and debt instruments and providing or settling loans and other forms of credit[8]

Therefore, the financial reporting is designed with the ultimate user of the information in mind, the saver or investor. With standardized financial reporting the readers of the financial statements can easily compare companies from different industries. While Arch Coal and Google are very different organizations, they both produce comparable financial reports that are subject to the same rules. As a result, investors can more easily decide whose IOU they want to take a chance on. Imagine how complicated this task would be for savers if each borrower invented its own reporting terminology and methodology.

You should have already memorized a good deal of the financial accounting language that we will use throughout the rest of this textbook. If not, you should now be convinced why this is so important, so if you are not yet proficient, please redouble your efforts. Before you begin to apply this new language, you must adopt the financial accounting mindset. For the remainder of this class, please restrict yourself to the language of the paradigm when discussing (or thinking about) financial accounting. Specifically, use the memorized terms properly, i.e. do not say “cost” when you mean “expense”, and do not use colloquial language like “making money” which has no meaning in financial accounting. Language is important and it is how you identify yourself as a serious member of a scientific community. Refrain from making absolute statements. For example, instead of saying “it is” and use “it appears,” and when possible quantify your observations; stating that Net sales increased by 25% from 2010 to 2011 is much more precise than declaring that Company X’s sales are “growing like crazy.”

Preparing Financial Statements

In this section you will learn how to create the Income Statement, Statement of Retained Earning and the Balance Sheet. These three statements are required components of GAAP financial reporting. A financial report will include the Statement of Cash Flows, which you will learn later in this text, along with other required disclosures (full disclosure principle) that are referred to as Notes to Financial Statements, which we will only discuss lightly in this text[9]. A financial report must include all of the required components or it is invalid. It is not acceptable to merely present one or two items, for example, an Income Statement and Balance Sheet. An incomplete financial report could mislead a reader; therefore, they are prohibited by GAAP.

All of the spreadsheets used in this Chapter are available in Google Docs (https://docs.google.com/templates?view=public&authorId=16126875423278426092). You will need to register for a free account to use the spreadsheets. The following is a YouTube companion lecture to this textbook http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LsOGkKbZvlg. The steps we will follow for preparing financial statements are as follows:

1. Prepare a Trial Balance as of the last day of the period.

2. Prepare the Income Statement (Revenues and Expenses) for the entire period.

3. Prepare the Statement of Retained Earnings for the entire period (Beginning Retained Earnings and Dividends).

4. Prepare the Balance Sheet as of the last day of the period (Assets, Liabilities and Paid in Capital accounts).

Step 1: The List of Accounts

Time to begin putting your memorization skills to the test. Please copy the following list of accounts onto green bar paper, exactly the way you see it here. Please make sure to carefully copy the numbers and agree your total to the total in the book. Next, fill in the “Account Type” column based on you memorization of terminology in Chapter 1. You are doing an after the fact Chart of Accounts, generally you would have set up the accounts and account types before any transactions were entered into your accounting system, but we are doing this because we are jumping to the financial statements before we learn to analyze transactions.

Table 2.2 List of Accounts

If you need to refer back to Chapter One to determine the proper account type, then this is an indication that your memorization needs work. The next step is to categorize the balance in each account as either a Debit or Credit. The accounts included here are for the legal entity of Lizzie Incorporated and are not comingled with any other entity (the owner). It is further assumed that we are using the monetary unit of U.S. Dollars as the unit of measurement; things that cannot be measured in Dollars are not in the financial statements. Furthermore, it is assumed unless otherwise stated, that Lizzie Incorporated is a going concern and is not expected to go out of business before it can realize its assets in the normal course of business.

Table 2.3 Trial Balance

Copy the format of the Trial Balance onto a fresh sheet of green bar columnar paper. Categorize the accounts based on your previous memorization work. We always start with a trial balance because if our debits and credits do not equal, then there is a problem with our accounting records and we should not even attempt to create financial statements.

After you match the balance in Table 2.3, you are ready to create your first three financial statements. Make sure you have three sheets of columnar paper available, accountants hat it when you put two financial statements on the same sheet of paper! As you use an account on the Trial Balance, put a check mark next to it. Each account will be used only one time on the financial statements and all accounts will be used.

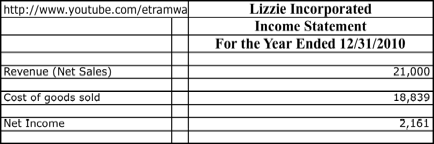

Table 2.4 Income Statement

Pay special attention to the heading of each financial statement. This tells the reader exactly what they are looking at and frees you from the responsibility of explaining your methodology and the definitions of your variables. Copy the format of this table onto your columnar paper and attempt to bring over the necessary accounts on your own. When you are done, compare your work to the table before going to the next statement.

Notice the date on this statement. It tells the reader of the statement that it covers a period of one year, from January 1 through December 31, 2010. If you merely wrote, “As of 12/31/2010”, the reader of the statement would have no way to know what period it covered.

Table 2.5 statement of Retained Earnings

This statement (as well as the Statement of Cash Flows) must cover the same period as the Income Statement. Beginning Retained Earnings and Dividends come from the Trial Balance (zero balance) while Net Income is from the Income Statement. How would the financial statements have been effected if dividends had been declared and paid during 2010?

Table 2.6 Balance Sheet

Finally, prepare the Balance Sheet using the above guide. Notice the date is as of the last day of the period. This is because the Balance Sheet represents only a snapshot in time, not all activity over the period (i.e. the Cash is the balance at Midnight on 12/31/2010). Notice that we made it easy for the reader to identify both current and long-term assets and liabilities.

Please practice this problem over and over until you can complete it in less than 15 minutes. It is very simple, but this is the foundation of your knowledge base and you must be able to complete this work without thinking about it too much

Qualities of Useful Information

The following is a direct quote from FASB’s Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 2.

Relevance and reliability are the two primary qualities that make accounting information useful for decision making. Subject to constraints imposed by cost and materiality, increased relevance and increased reliability are the characteristics that make information a more desirable commodity—that is, one useful in making decisions. If either of those qualities is completely missing, the information will not be useful. Though, ideally, the choice of an accounting alternative should produce information that is both more reliable and more relevant, it may be necessary to sacrifice some of one quality for a gain in another.

To be relevant, information must be timely and it must have predictive value or feedback value or both. To be reliable, information must have representational faithfulness and it must be verifiable and neutral. Comparability, which includes consistency, is a secondary quality that interacts with relevance and reliability to contribute to the usefulness of information. Two constraints are included in the hierarchy, both primarily quantitative in character. Information can be useful and yet be too costly to justify providing it. To be useful and worth providing, the benefits of information should exceed its cost. All of the qualities of information shown are subject to a materiality threshold, and that is also shown as a constraint.[10]

GLOSSARY OF TERMS (Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 2

Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information)

Bias

Bias in measurement is the tendency of a measure to fall more often on one side than the other of what is represents instead of being equally likely to fall on either side. Bias in accounting measures means a tendency to be consistently too high or too low.

Comparability

The quality of information that enables users to identify similarities in and differences between two sets of economic phenomena.

Completeness

The inclusion in reported information of everything material that is necessary for faithful representation of the relevant phenomena.

Conservatism

A prudent reaction to uncertainty to try to ensure that uncertainty and risks inherent in business situations are adequately considered.

Consistency

Conformity from period to period with unchanging policies and procedures.

Feedback Value

The quality of information that enables users to confirm or correct prior expectations.

Materiality

The magnitude of an omission or misstatement of accounting information that, in the light of surrounding circumstances, makes it probable that the judgment of a reasonable person relying on the information would have been changed or influenced by the omission or misstatement.

Neutrality

Absence in reported information of bias intended to attain a predetermined result or to induce a particular mode of behavior.

Predictive Value

The quality of information that helps users to increase the likelihood of correctly forecasting the outcome of past or present events.

Relevance

The capacity of information to make a difference in a decision by helping users to form predictions about the outcomes of past, present, and future events or to confirm or correct prior expectations.

Reliability

The quality of information that assures that information is reasonably free from error and bias and faithfully represents what it purports to represent.

Representational Faithfulness

Correspondence or agreement between a measure or description and the phenomenon that it purports to represent (sometimes called validity).

Timeliness

Having information available to a decision maker before it loses its capacity to influence decisions.

Understandability

The quality of information that enables users to perceive its significance.

Verifiability

The ability through consensus among measurers to ensure that information represents what it purports to represent or that the chosen method of measurement has been used without error or bias.

[1] Retrieved from http://www.fasb.org/facts/index.shtml#structure on May 28, 2011.

[2] http://www.sec.gov/about/whatwedo.shtml

[3] http://www.aicpa.org/About/Pages/About.aspx

[4] See http://www.fasb.org/jsp/FASB/Page/SectionPage&cid=1176156317989

[5] This is a great definition of variables in scientific study from the U.S. Department of Education’s website http://nces.ed.gov/nceskids/help/user_guide/graph/variables.asp

[6]1. Able to be trusted as being accurate or true; reliable: "clear, authoritative information".

2. (of a text) Considered to be the best of its kind and unlikely to be improved upon

[7] http://www.ifrs.org/Home.htm

[8] Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 8

[9] The Statement of Comprehensive Income will be covered in Intermediate Accounting.

[10] http://www.fasb.org/cs/BlobServer?blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs&blobkey=id&blobwhere=1175820900526&blobheader=application%2Fpdf

No comments:

Post a Comment